Curry's paradox

Curry's paradox is a paradox that occurs in naive set theory or naive logics, and allows the derivation of an arbitrary sentence from a self-referring sentence and some apparently innocuous logical deduction rules. It is named after the logician Haskell Curry.

It has also been called Löb's paradox after Martin Hugo Löb.[1]

Contents |

Natural language

Claims of the form "if A, then B" are called conditional claims. Curry's paradox uses a particular kind of self-referential conditional sentence, as demonstrated in this example:

- If this sentence is true, then Germany borders China.

Even though Germany does not border China, the example sentence certainly is a natural-language sentence, and so the truth of that sentence can be analyzed. The paradox follows from this analysis. First, common natural-language proof techniques can be used to prove that the example sentence is true. Second, the truth of the example sentence can be used to prove that Germany borders China. Because Germany does not border China, this suggests that there has been an error in one of the proofs. Worse, the claim "Germany borders China" could be replaced by any other claim, and the sentence would still be provable; thus every sentence appears to be provable. Because the proof uses only well-accepted methods of deduction, and because none of these methods appears to be incorrect, this situation is paradoxical.

Proof that the sentence is true

The following analysis is used to show that the sentence "If this sentence is true, then Germany borders China" is itself true. The quoted sentence is of the form "If A then B" where A refers to the sentence itself and B refers to "Germany borders China". Within the naïve logic that Curry was working on, the method for proving a conditional sentence is to assume that the hypothesis (A) is true, and then prove from that assumption that the conclusion (B) is true.

Assume A is true. Because A refers to the overall sentence, therefore assuming A is true is the same as assuming that the statement "If A then B" is also true. Because A is true, therefore B is true. Assuming A is true is therefore enough to guarantee that B is true regardless of the truth of statement B.

The paradox

In a naïve logic, the sentence itself, denoted A, is true. The sentence is of the form "If A then B". Since A is true, therefore "If A then B" is true. We then apply modus ponens to show that B is true; but this is impossible, because B is "Germany borders China", which is false.

Formal logic

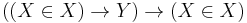

The example in the previous section used unformalized, natural-language reasoning. Curry's paradox also occurs in formal logic. In this context, it shows that if we assume there is a formal sentence (X → Y), where X itself is equivalent to (X → Y), then we can prove Y with a formal proof. One example of such a formal proof is as follows.

1. X → X

- rule of assumption, also called restatement of premise or of hypothesis

2. X → (X → Y)

- substitute right side of 1, since X is equivalent to X → Y by assumption

3. X → Y

- from 2 by contraction

4. X

- substitute 3, since X = X → Y

5. Y

- from 4 and 3 by modus ponens

Therefore, if Y is an unprovable statement in a formal system, there is no statement X in that system such that X is equivalent to the implication (X → Y). By contrast, the previous section shows that in natural (unformalized) language, for every natural language statement Y there is a natural language statement Z such that Z is equivalent to (Z → Y) in natural language. Namely, Z is "If this sentence is true then Y".

Naive set theory

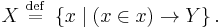

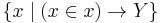

Even if the underlying mathematical logic does not admit any self-referential sentence, in set theories which allow unrestricted comprehension, we can nevertheless prove any logical statement Y by examining the set

The proof proceeds as follows:

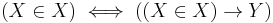

- Definition of X

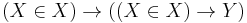

- from 1

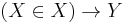

- from 2, contraction

- from 1

- from 3 and 4, modus ponens

- from 3 and 5, modus ponens

Therefore, in a consistent set theory, the set  does not exist for false Y. This can be seen as a variant on Russell's paradox, but is not identical. Some proposals for set theory have attempted to deal with Russell's paradox not by restricting the rule of comprehension, but by restricting the rules of logic so that it tolerates the contradictory nature of the set of all sets that are not members of themselves. The existence of proofs like the one above shows that such a task is not so simple, because at least one of the deduction rules used in the proof above must be omitted or restricted.

does not exist for false Y. This can be seen as a variant on Russell's paradox, but is not identical. Some proposals for set theory have attempted to deal with Russell's paradox not by restricting the rule of comprehension, but by restricting the rules of logic so that it tolerates the contradictory nature of the set of all sets that are not members of themselves. The existence of proofs like the one above shows that such a task is not so simple, because at least one of the deduction rules used in the proof above must be omitted or restricted.

Combinatory logic

In the study of illative combinatory logic, Curry in 1941[2] recognized the implication of the paradox as implying that, without restrictions, the following properties of a combinatory logic are incompatible:

(i) Combinatorial completeness. This means that an abstraction operator is definable (or primitive) in the system, which is a requirement on the expressive power of the system.

(ii) Deductive completeness. This is a requirement on derivability, namely, the principle that in a formal system with material implication and modus ponens, if Y is provable from the hypothesis X, then there is also a proof of X → Y.[3]

Discussion

Curry's paradox can be formulated in any language meeting certain conditions:

- The language must contain an apparatus which lets it refer to, and talk about, its own sentences (such as quotation marks, names, or expressions like "this sentence");

- The language must contain its own truth-predicate: that is, the language, call it "L", must contain a predicate meaning "true-in-L", and the ability to ascribe this predicate to any sentences;

- The language must admit the rule of contraction, which roughly speaking means that a relevant hypothesis may be reused as many times as necessary; and

- The language must admit the rules of identity (if A, then A) and modus ponens (from A, and if A then B, conclude B).

Various other sets of conditions are also possible. Natural languages nearly always contain all these features. Mathematical logic, on the other hand, generally does not countenance explicit reference to its own sentences, although the heart of Gödel's incompleteness theorems is the observation that usually this can be done anyway; see Gödel number. The truth-predicate is generally not available, but in naive set theory, this is arrived at through the unrestricted rule of comprehension. The rule of contraction is generally accepted, although linear logic (more precisely, linear logic without the exponential operators) does not admit the reasoning required for this paradox.

Note that unlike the liar paradox or Russell's paradox, this paradox does not depend on what model of negation is used, as it is completely negation-free. Thus paraconsistent logics can still be vulnerable to this, even if they are immune to the liar paradox.

The resolution of Curry's paradox is a contentious issue because resolutions (apart from trivial ones such as disallowing X directly) are difficult and not intuitive. Logicians are undecided whether such sentences are somehow impermissible (and if so, how to banish them), or meaningless, or whether they are correct and reveal problems with the concept of truth itself (and if so, whether we should reject the concept of truth, or change it), or whether they can be rendered benign by a suitable account of their meanings.

Linear logic disallows contraction and so does not admit this paradox directly, but one must remove its exponential operators, or else the paradox reappears in a modal form.

See also

References

- ^ Barwise, Jon and John Etchemendy 1987: The Liar, p. 23. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Curry, Haskell B. 1941: The Paradox of Kleene and Rosser. Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 50: pp 454–516.

- ^ Stenlund, Soren 1972: Combinators, λ-Terms and Proof Theory, p. 71. D. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht, Holland.

External links

- Curry's paradox entry by J. C. Beall in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Grossman, Jason, Australian National University: A Proof that Penguins Rule the Universe. A brief and entertaining discussion of Curry's paradox.

- Relevant First-Order Logic LP# and Curry's Paradox